Perfect freedom is reserved for the man who lives by his own work,

and in that work does what he wants to do.

I think it was in an installment of his Noise Level column that John Brunner made the claim that when science fiction authors got together they mostly talked about money. Now I’m not about to disagree with a statement like that given Brunner wrote science fiction for a living and was certainly in a position to know what his fellow authors said and did. Even so I do have to wonder if his views were biased by his own preoccupations. He certainly did write about the financial aspects of being a published author more than any other SF professional I’m familiar with.

I suspect this obsession with financial success was in large part due to his origins. The Brunner family started a company called Brunner Mond way back in 1873 (this company later on merged with a number of others to form ICI) so they were reasonably well-to-do, though perhaps not as well off as they had been by the time our Brunner was born in 1934. There are claims that despite the family having money none of it was passed on down to John Brunner once his school fees had been paid. Why this might be so I can’t say for certain though it’s possible the family disliked his lifestyle and/or politics. John Brunner was quite left-wing in many of his views, in particular he was quite anti-nuclear and vehemently opposed the war in Vietnam, opinions which might not have sat well with people who earned their living from a chemical company like Brunner Mond. It’s also possible that Brunner preferred to not receive what he may have perceived as ‘dirty’ money and became obsessed with achieving financial success without relying on his family.

Regardless of why he felt the need to do so I’m pleased he wrote about the financial side of the writing business as much as he did because the nuts and bolts of the trade fascinate me and I love reading descriptions of how the system once worked by those on the inside. As I assume I’m not the only one interested in such things I’ve reprinted one of the best examples of Brunner’s behind the scenes coverage here. It originally appeared in Australian Science Fiction Review #9 (published by John Bangsund way back in April 1967). It was a slightly updated version of an article that had already been published in Vector, the official journal of the British SF Association, a year or so before (just how much had been changed I can’t say as I don’t happen to own a copy of the relevant issue of Vector). To put this article into context I need to point out that Brunner’s professional career up until the writing of this article essentially fitted into what I like to think of as the transitory period of SF publishing.

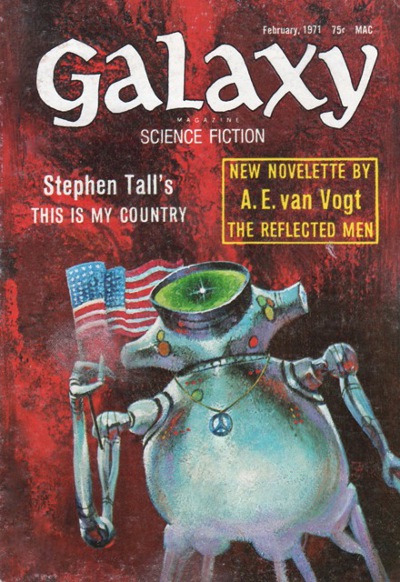

This transitory period in SF publishing occurred when it became possible for an author to make appreciable amounts of money from magazine, paperback, and hardcover sales. Up until the end of WWII very few writers of science fiction were able to sell their stories to any market other than the magazines. Hardcover books were limited to the likes of Verne, Wells, and Burroughs until the rise of specialty hardcover houses such as Gnome Press, Prime Press, and Shasta Publishers in the late forties. Paperback science fiction didn’t become a force until well into the fifties at which point the amount of SF in softcover rose dramatically. This ushered in the transitory period during which SF authors could make a living by a careful combination of magazine, paperback, and hardcover sales. However the rise of the paperback corresponded with the decline of the fiction magazine and by the end of the seventies there were too few SF magazines left for sales to this market to be a significant portion of the average author’s income. During the period Brunner is writing about both authors and publishers were still feeling their way towards their part in the later paperback dominance of the industry.

To give everybody at least some idea of what all those sums Brunner quotes in the later part of his article might mean in current terms I’ve included estimates of what the money equivalent would be fifty years later (all figures are either in UK pounds or US dollars). Hopefully that will give you some idea of how well off the average author was back then. On the other hand I wouldn’t try to strain for a comparison with current conditions given how different the publishing industry is in this world of tomorrow. For example making those sort of comparisons won’t mean much in in relation to the earnings of anybody trying to make it as a self-published author.

I also like to reiterate Brunner’s comment about taking care when basing generalisations on this article. A lot of the minor details, such as a wife as who doesn’t want to go back to working or an author getting into a tangle with customs over the value of a manuscript, are clearly lifted from John Brunner’s own life (though, that said, I do recall another British author who mislabelled one of the manuscripts he mailed to the US and ended up in a ‘situation’ due to this). On the other hand the two Frishblitz children are complete fabrications as nothing I know about John Brunner suggests to me that he ever had, wanted, or liked children.

Given the length of this article and the many interesting details Brunner included I’ve interrupted him in a number of places to add some extra detail, or my own reactions to certain of his claims. Hopefully you’ll find these additions worth the interruption.

And now on with the show:

The Economics of SF

by John Brunner

“In an earlier instance the Meredith agency did sell the picture rights to a book then unwritten. That one, Evan Hunter’s Mothers & Daughters, has now been completed, and German rights have just gone to Kindler Verlag, in a deal closed with their representative here, Maximilian Becker, for a record $17,000 advance. Also, Corgi have just acquired British paperback rights on a £15,000 advance.”

Daniel J. Boorstin: The Image, p. 158)

It so happens that I’m represented by the Scott Meredith Agency which pulled this trick. Every now and again I feel tempted to photostat that excerpt and send it to Joe Elder, who handles my work, with a terse note asking what Evan Hunter has that I haven’t (apart from $17,000 and £15,000).

It’s small wonder that most people have an entirely false impression of what authors make, and this impression is distorted even further when one comes down to SF, a thoroughly anomalous field in other aspects than its content.

Let’s start by getting some of our perspectives straight. First, as to writers and their incomes in general: the British Society of Authors is conducting a survey at present which will clear up many misunderstandings when the findings are made public. Consider, meantime, that a reliable source (the Bulletin of the Authors Guild of America) has published an estimate that there are 250 full-time writers in the whole of the United States.

I’ll repeat that: 250. Out of a population approaching two hundred million. The remainder are at least partly supported by such jobs as magazine editing, reporting, permanent feature assignments involving non-writing activity, or hold down a professional post to which their writing is secondary. (Advertising is one of the current havens; it’s a bit like the jazz greats of the thirties who kept joining and leaving the Ted Lewis band.)

A young writer recently received tremendous acclaim from the British press. I’ve read the book he got it for, and allowing for slight exaggeration I think the praise was merited. I’ve lent my copy to somebody so I can only quote a sample from memory: “I doubt,” said one critic, “if there are half a dozen people who can match” Mr. X’s prose. He made the headlines recently when a publisher offered to pay him what amounts to a salary for the next two years, on condition they are given a couple of books they can publish. Amount of that “salary”? £800 (£13,803 in 2017). And he was probably glad to get it. Brother! Given a reasonable amount of overtime, he could probably collect more working on a building site!

Now the generous publisher isn’t buying his entire thinking time, of course. But he’s buying the cream of Mr. X’s output, and if Mr. X is halfway honest he’ll be turning down supplementary earnings which would infringe on the thinking time needed to create books reflecting his true abilities. Many – perhaps most – writers never stop working; everything they do from breakfast to bedtime, everything they read from advertisements to poetry, everything they see or hear or smell or touch or taste gets mortared into the foundations for their subsequent output. Isaac Asimov wasn’t joking when he said writing has the characteristics of an addictive drug. Once you’re hooked on it properly, your life revolves around it in the same way a junkie’s revolves around his next fix. It can be physically unpleasant to be deprived of the opportunity to write. (Believe me.)

What of the writer who , by misfortune, has a temperament inclining him towards SF? Well… I’m one, and a very atypical one, so most of the following remarks must be read as applying to me personally and generalizations should be made there from very tentatively indeed. Nonetheless, I feel they may be of interest as a kind of case-history cum guided tour of a thorny question.

Cardinal fact: SF is a minority taste, to the extent that hitherto one has been able to say it’s read by one person in every thousand of the English-speaking population. (I refer to habituated readers, and not to those who are exposed to an occasional freak best-seller serialised in the Saturday Evening Post.) For instance, I recall seeing Astounding’s public estimate at some 185,000 in a country of about as many million: similarly, the Atlas reprint edition used to sell about 45,000 in Britain.

There is a slow upward trend in these figures at present, due to such causes as the adoption of SF by “respectable” houses like Penguin and the discovery by literate readers that there are literate writers in the field. The impact of this has not yet been sufficient to alter much of the SF writer’s life. We will assign Arthur Clarke, John Wyndham, John Christopher and some few others to the stratospheric altitudes of the movie world (every writer dreams of selling film rights on every book he produces), and concentrate on the somewhat more mundane levels where the majority of the writers who appear in your Favourite Magazines float around.

(Doctor Strangemind: This article was originally written with a British audience in mind so it’s hardly surprising that he only mentioned British authors in this list. It’s also likely that Brunner didn’t want to include any US authors on the not unreasonable basis that he didn’t know enough to do more than guess at who might be earning enough to be added to his list. Even today, with all the advantages of 20/20 hindsight, I’d be hard pressed to name any US authors apart from perhaps Robert Heinlein and Isaac Asimov as doing that well back in the early sixties.)

As pointed out, there is a three-to-one difference in the size of the audience for SF when you compare Britain and the USA. It’s reflected fairly accurately in the rates paid. To try to make a decent living by selling nothing but SF in Britain would be impossible. (John Lymington appears to have found a sort of solution to this, but I have no information regarding other earnings he may have.)

Example: Gollancz’s basic advance on a hardcover edition – to which royalties will be added after a very long lapse of time – is £100 (£1,725 in 2017). I received that for both The Brink, in 1959, and No Future In It, in 1962. Ace, not the largest or most prosperous of American paperback firms, would put down $1,000 ($7,186 in 2017) for the same manuscript, or about £350 (£6,037 in 2017). As to magazines, I recall how pleased I was when Ted Carnell gave me a bonus on a story he published by raising my rate from two guineas to £2.5.0 per thousand words. Near as dammit, two guineas is $6 ($43 in 2017). As far as I know the lowest rate paid in recent years by am American SF magazine has been that from Fantastic at 1.5 cents per word – i.e. $15 per thousand ($108 in 2017), or 2½ times as much.

The highest rate is Analog‘s 4 cents a word, plus a cent a word bonus for topping the An Lab, or half a cent for coming second. The less pretentious of the men’s magazines go no lower than a nickel a word – a cent higher that the best offered by an SF magazine in other words.

It’s a minor miracle that there are so many writers in the SF field, isn’t it?

There are basically two ways in which you can keep afloat in SF without resorting to devious expedients like writing continuity for a comic strip (e.g. Jack Williamson for Beyond Mars, Harry Harrison and heaven knows who else for Flash Gordon) or beating your brains out on a TV serial (a common disaster among American SF writers, I gather, but not so popular in Britain).

The first is to get out of the United States, if that’s where you happen to be, and settle in some country where a phony exchange rate stretches your dollar earnings. I live in Britain but almost exactly 90% of my income is from America.

The second is to be prolific as possible, and that’s a matter of temperament. I’m lucky; I have a very high rate of output because I actually enjoy the physical process of writing, and get unhappy when I’m kept away from my typewriter. I’ve been writing about eight books a year lately, and banking on selling six of them to get me a decent living. But I cant keep that up forever; I was just about at the end of my tether when I started getting serializations in American magazines – something I’d previously failed to secure – and was able to contemplate reducing my schedule because of the extra income thus obtained from the same investment of effort.

(Doctor Strangemind: I do wish Brunner had been clearer in his description at this point because one possible interpretation of his comment about writing eight books each year and selling six is that he was failing to sell 25% of the novels he completed. Surely after a year or two of frenetic production which results in only a 75% success rate an astute author learns to recognise what is likely to sell and what is likely to be passed over? Surely by year three a reasonably astute author can spot unsaleable product in its formative stage and not proceed. Surely?

Anyway, checking the listings for John Brunner on the The Internet Speculative Fiction Database doesn’t shed much light on the matter either. According to the listings there the Brunner SF novels published prior to the writing of this article amounted to the following:

1959 – 3

1960 – 4

1961 – 2

1962 – 2

1963 – 6

1964 – 2

1965 – 6

Clearly this is well short of the 8 Brunner claimed he was writing each year, and indeed is even short of the 6 he claimed he was selling. So either he was exaggerating or he was turning out as much non-genre material as he was SF. I’ve certainly seen mention of a couple of early non-genre novels, The Crutch of Memory – Barrie & Rockliff (1964) & Wear the Butcher’s Medal – Pocket (1965), so who knows what else might be lurking out there in the great paperback graveyard.)

(There’s a third solution: to live on bread and cheese in one room, preferably in a warm part of the country to save on heating bills. Some people can stand it. I can’t. When I first moved to London from my home, my earnings as a writer averaged four pounds a week and I was renting a two-guinea room. I gave up and went to work for Sam Youd and it was two and a half years before I plucked up the courage to try freelancing again – by which time I was married and Marjorie was still working, so it wasn’t so risky… This suggests another solution I’s overlooked: marry an heiress. Difficult. So few heiresses appreciate SF.)

All this stems from some comments in Vector #32, where Ken Slater was explaining the facts of life to those of his customers who wanted to know why they couldn’t have the Ballantine edition of The Whole Man (Telepathist in the UK) instead of the Faber hardcover edition to be followed in about two years time by a Penguin.

Well it’s nice to know that so many people are eager to read my stuff… and I’m not even much hurt by the fact that they aren’t eager enough to pay eighteen shillings for the privilege of reading it now, this minute. Among my colleagues I’m regarded as something of a subversive for approving of original paperbacks – but why not? After all, there are few books you read more than once. A typical novel is likely to give you an evening’s entertainment at the speed most moderately literate people read. It seems reasonable to pay for it what you’d pay for a seat at the local cinema or a gallery seat in a theatre; say 3/6 to 7/6, the price of a current paperback.

But look at the matter from the author’s point of view. Look at it, specifically, from mine. Turning out up to eight books a year means that at least one of those books is going to be really good; the rest will range from competent to barely passable, or even lousy, and would benefit immensely from being put on the shelf in manuscript form until I have the time and the inclination to revise, polish, or perhaps scrap them.

If, out of a given book, I’m making only £350 (£6,037 in 2017) less the 10% which the agent takes (which is what happens if I sell it solely to an American paperback publisher who then markets his own edition in Britain), I have to keep churning them out. From the outside, I should perhaps explain, writing books looks like a cheap way of running a business, but I often find when making up my tax returns that my deductible expenses – i.e. those incurred directly in connection with my work – have used up 20% of my gross income.

(Doctor Strangemind: I do wish he had added a little more detail at this point. I’m very curious to know just what those deductible expenses were that using up so much of his income. I strongly suspect, given some of the anecdotes I’ve read about him, that he had a tendency towards extravagance, but perhaps I’m being entirely unfair and it was prosaic matters such as the posting of manuscripts across the Atlantic which was eating up his funds.)

The sales of that American edition in Britain add practically nothing to my earnings; the book comes in, months or years after its first appearance in the States, attracts no attention whatever, isn’t reviewed anywhere, and does no more than spoil my chances of selling the same work to a publisher in this country. As a matter of fact, British sales may well add nothing to my earnings because the American publishers simply want to get their back stock out of the warehouse to make room for newer items. This is called ‘dumping’.

(Doctor Strangemind: Now this part really confuses me. I was under the impression that there was was some sort of legal agreement in place to ensure US publishers couldn’t sell in Britain & the Commonwealth and visa-versa. However Brunner is clearly suggesting he was dealing with US publishers who were doing just that. A quick look on The Internet Speculative Fiction Database however shows that nearly all his early US novel sales went to Ace. The only exceptions I can find are these four:

The Dreaming Earth – Pyramid (1963)

The Whole Man – Ballantine (1964)

The Squares of the City – Ballantine (1965)

The Long Result – Ballantine (1966)

I can’t see any of these publishers participating in a practise like ‘dumping’ that seems to be, at the very least, on the edge of legality. I can only wonder then if the books he is referring to were the non-genre novels whose existence I was speculating about earlier?

Not only that but he seems to think it unfair that he saw no money from this ‘dumping’ practise he claims was going on. If any publisher were actually selling to the remainder market (which seems the most likely explanation if something was indeed going on) then why does Brunner think he might earn anything from the process at all? Again, as I understand it, books are only remaindered after a contract is terminated and I doubt a publisher doing something as dubious as selling any leftover copies on the cheap is going to be keen to give the author a cut and thus provide the author with hard evidence of this practise. It all seems rather curious.)

By signing a contract which confines distribution rights of the American edition strictly to territories outside the sterling area (the wording varies, but this is an example), I can hang on to the chance of additional sales. Suppose, as happened with The Whole Man, Faber buys the manuscript: I get, eventually, another couple of hundred quid in small chunks; I get the chance of a Science Fiction Book Club selection which adds a bit more; I get the chance of a paperback sale in Britain which adds a great deal more; over a period of about three to five years I’ve comfortably doubled the proceeds. I know it’s an awful nuisance to have to wait for the Penguin edition in 1968 or whenever before you can read this book that all your fan friends in Oshkosh or Walla Walla are raving about. But it contains a blessing in disguise: by 1968 I shall have put together my long-awaited epic, Soul Slaves of the Umpteenth Continuum, and its going to make all my previous work look like Kid-dee Com-ics. Up until now force of circumstance and the wolf at the door have conspired to make me postpone work on it.

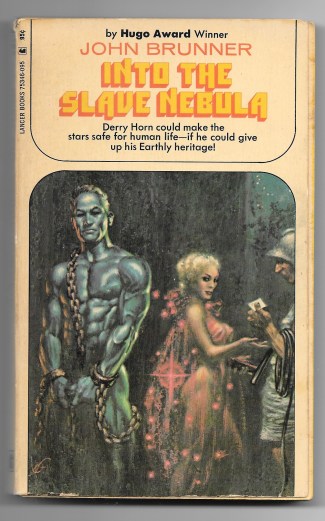

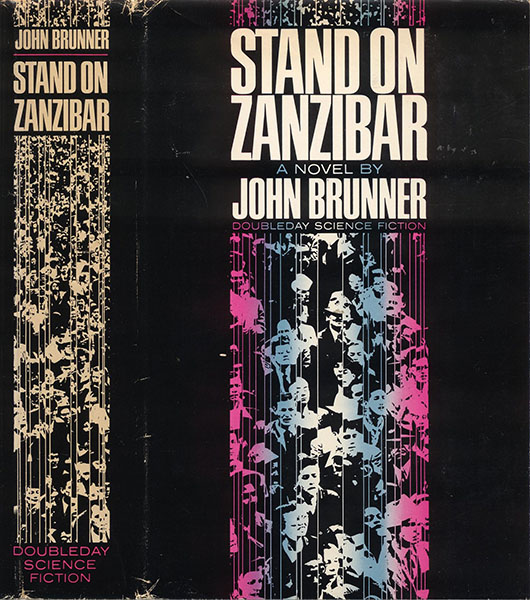

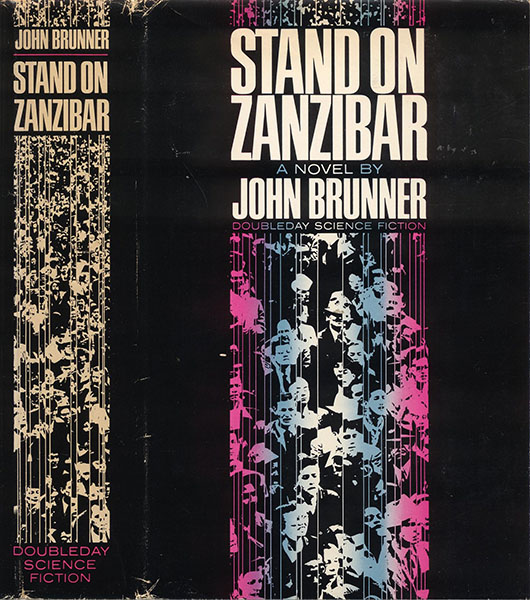

(Doctor Strangemind: Brunner was clearly joking about writing the above named long awaited epic but on the other hand his four major novels; Stand On Zanzibar (1968), The Jagged Orbit (1969), The Sheep Look Up (1972), & The Shockwave Rider (1975) were just a few years in the future at this point so the comments above are far closer to the truth than anybody realised in 1967.)

More seriously, here are some hard figures by which you can gauge the economics of the field as they apply to a competent, diligent writer of average output and adequate persistence. Let’s call him Theokurt Frishblitz in honour of some of my personal idols.

(Doctor Strangemind: No, I’ve no idea who these personal idols Brunner was alluding to when he named his character Theokurt Frishblitz, possibly nobody but Brunner would ever have any idea. Still, feel free to speculate as I’d be interested in any suggestions.)

In Year One of his career Mr. Frishblitz breaks through the hitherto impenetrable wall of rejection slips, revises his long-standing opinion of all editors as purblind nits, and sells a short story to Unused Planets, a British magazine with a high reputation and low rates, Proceeds: about £10 (£172 in 2017).

Encouraged, he stands the editor a drink and makes a note in his diary: To Business Expenses, 3/6. The editor is favourably impressed with his idea for a novelette and promises it the cover if it turns out okay. He also suggests some alterations and improvements in the story line. Mr. Frishblitz gets it right on the second submission. Proceeds: about £50 (£862 in 2017).

One or two or possibly more stories later, he conceives his first novel, and offers it as a serial. It clicks. Proceeds: about £150 (£2,587 in 2017).

Provided he has had the good sense to to make two carbons of this novel he can now cast covetous eyes on the U.S. Market. So far he’s been getting nothing but bounces – from stories which Unused Planets thereupon bought at the minimal British rates. But a novel, surely, which has been serialised…?

Mr. Frishblitz wraps it up, fills out the customs declaration with an optimistic assessment of the book’s value (which will later cause some wrangling and delay in U.S. Customs), and mails it to Trump Books Inc., a small but voracious paperback house in New York with an enormous output of SF. It comes back, much later, with a reasonably kind letter saying they published more or less the same story in 1937 and just reprinted it, but would welcome more of his work; they pay a standard advance of $1,000 ($7,186 in 2017) and would rather the customs slip was marked NO COMMERCIAL VALUE because it makes things simpler at the New York end.

At the end of Year One Mr. Frishblitz tots up his earnings. Rejections included he’s written some hundred thousand words or so – which is a lot of words if you count them one by one. It’s even more if you take re-writes into account. He’s made about £250 (£4,312 in 2017), which is good going for his first year.

What to do? Well… how about an agent? He applies to Scotfree Cheeryble Inc., who – according to The Writer’s Annual – had the highest turnover in America last year and sold one book for a total of $175,000. A note comes back saying, with devastating honesty, that Cheeryble aren’t much interested until a writer is making $1,000 p.a. on his own; then they’ll consider accepting him.

He already knows how much $1,000 is – he worked it out when he got the letter from Trump Books. It’s £357. Anyway, what does he want to give 10% of his earnings for? He’s doing okay, isn’t he?

We-ell…

Let’s skip the interval during which he learns the basic economics of the job and jump to the year in which he quits his regular employment to take a flyer as a freelance; lets say that this is Year Five of his writing career. He’s saved up enough to risk an initial drop in his total income, though his wife is afraid of having to go back to work, and his two children are more expensive than racehorses to feed and keep. The accumulated frustration left over from part-time work, interrupted by having to go to the office every day, lets go with a surge and carries him through the first half of the year with three novels and a couple of good novelettes.

He sells the novelettes – totaling 30,000 words – to U.S. magazines and makes from them what he made in his first year’s work: £250 (£4,312 in 2017). He sells the first two novels to Trump, which he now regards as a safe market, for $1,000 ($7,186 in 2017) and $1250 ($8,982 in 2017) respectively.

Novel three comes back with a regretful note to say it’s below standard, try again.

To Mr. Frishblitz this is a sore blow. He does no more work for a month through worrying; then starts worrying about not working; then the worry fouls him up for a further month, during which time the children eat the proceeds of the sales so far this year. By year’s end he’s recovered enough to have completed a fourth novel. Proceeds this year amount to an acceptable £1500 (£25,880 in 2017), but he’s written about 300,000 words for that, some of which hasn’t found a home, and he’s not sure he can manage the wordage equivalent of five novels every year from now on. His imagination is getting a bit tattered around the edges and what he really wants to do is spend a month researching a magnum opus about colonising the ocean-bed, whereas Trump Books are asking for a sensational novel about adultery in free fall, tentatively titled Peyton Planet.

If he has any sense, this is when he writes to Cheeryble Inc. again. He has the sales behind to make them interested, but he lacks the specialised knowledge to exploit himself.

Lets wish him luck and see how he’s doing in Year Ten.

In this year he writes three books, one of them on commission from a publisher who bought an earlier novel. This is a comfortable pace to write at; it allows time for adequate research, second thoughts, re-reading, and if necessary complete revision which generally permits him to make sure that what he wraps and mails is as good as he can make it. Proceeds are roughly as follows:

The first novel appears, specially abridged by himself, as the lead short novel in a U.S. magazine and grosses $500 ($3,593 in 2017), then sells to a paperback house for $1500 ($10,779 in 2017) and to an English publisher for £150 (£2,587 in 2017), in the full-length version. The second is published as a two-part serial in a U.S. magazine, which pays $800 ($5,749 in 2017), and also goes to a paperback house for $1,500 ($10,779 in 2017), but is too far out to interest the rather conservative British publishers. Not to worry: number three marks two ‘first’ notches for him – his first U.S. hardback edition and his first double sale in Britain, to both hardback and paperback houses, as well as going to a U.S. paperback publisher, bringing some $2,000 ($14,372 in 2017) and £400 (£6,900 in 2017) from a single book. In addition he receives some small royalties from previous work, and there is no reason why novel number two should not later on find a home in Britain; moreover, by now he’s picking up the odd translation sale, and when the escudos, franks, marks, and whatsits are converted to sterling they add another 100-odd quid to the year’s total.

(Doctor Strangemind: This is where my point about there being a transitory period is best illustrated. It was only during those years between the early fifties and the eighties that it was possible to sell the same work in differing forms this many times.)

Year Ten therefore sees him comfortably established with an income of around £2,500 (£43,123 in 2017) plus past, future, and imponderable accretions from work not actually done during the year. He is doing very well considering the field he is in. Next year he may very well make less than £1,000 (£17,249 in 2017) because he breaks his wrist and can’t type, or he may make £10,000 (£172,493 in 2017) because his agent happens to be drinking within earshot of a film producer and seizes his chance on hearing the producer is looking for a science fiction property. He can’t tell. But he wouldn’t trade problems with anybody, He’s hooked on writing.

Mr. Frishblitz did everything right, and had the single essential attribute out of that list at the beginning of his career, which is persistence. He’s probably about thirty-five or forty; he gets half a dozen fan letters a year, is asked to speak at conventions, and when the BBC puts a programme together about SF they send someone around with a tape recorder and use two minutes forty seconds on the air. He’s okay. But if it hadn’t been SF he wanted to write – if it had been , say, TV serials and he sold an idea which caught on like Dr. Who – he might easily have made in the first two years enough to retire on, in a gracious modern house on Grand Bahama Island with his own private beach, and the seventeen Frishblitz books you so greatly enjoyed over the past ten years would never have been written at all.

Sometime I must ask Mr. Frishblitz which way he’d have preferred it to turn out back in Year One of his career…

If this article finds its way into the hands of any U.S. readers, they should remember the phoniness of the dollars-to-pounds exchange rate. In this country an annual income in the Frishblitz bracket will provide a comfortably furnished house, adequate food and clothing for a family of four, a medium priced car, and the occasional vacation abroad. At the current Stateside rate it would compare so badly with what one can earn in business that the writer’s wife would certainly leave him, unless she was desperately in love.

My guesstimate is that Mr. Frishblitz, living in the States, would have to earn some 50% more in order to survive, and at least 100% more to enjoy the U.S. Equivalent of Anglo-Frishblitz’s standard of living.

I couldn’t manage it. That’s why I live here. (Also I was born here, which counts for something…)