Before there was ‘major talent’, there was ‘complete unknown’.

It’s not hard to assume in today’s world of tomorrow that our best and brightest always appear to us first in novel form (and if you don’t find imagining your favourite author as a a small block of compressed wood pulp to be at least a little bit novel then you have a far wilder imagination that I will ever aspire to). I doubt matters are quite so cut and dried, that at least some currently well regarded authors served a short story apprenticeship before entering the dominant ecology of the paperback novel, but even so such an apprenticeship no longer seems to be de rigueur.

Of course aspiring authors of the 40s and earlier had little choice but begin in the magazines. But even as recently as the 60s, the decade when the science fiction magazine finally went underground, it remained common for new authors to scuttle about in the short fiction undergrowth like small mammals as they built sufficient reputation to tempt a paperback editor into taking a risk on them.

It is a pity that this lost world didn’t have some sort of science fictional David Attenborough creeping through the publishing undergrowth to breathlessly describe everything and anything he encountered. However, we do have on occasion the next best thing, that being the contemporary reviews of an emerging author’s earliest published works.

Contemporary reviews are always worth comparing with the way the work of a particular author is later viewed. When we read an early story by a somebody who has gone on to bigger and better work we tend to do so with our perceptions coloured by everything that has come since. A contemporary review of that story on the other hand is unencumbered by reputation and what somebody back then has to say about the early work of an author who today has a significant reputation can be surprising to say the least.

Take for example consider the following comments by US fan, Earl Evers, who reviewed the contents of the April 1964 issue of Fantastic Stories of Imagination in his fanzine, Zeen #2 within weeks of it hitting the shelves. In the process of reviewing this magazine, story by story, he had the following to say about what was one of Ursula K. Le Guin’s earliest published stories:

And just in case you find the scanned text a little difficult to read:

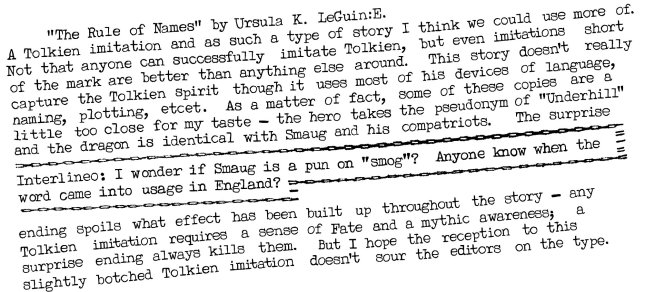

‘The Rule of Names by Ursula K. Le Guin

A Tolkien imitation and as such a type of story I think we could use more of. Not that anyone can successfully imitate Tolkien, but even imitations short of the mark are better than anything else around. This story doesn’t really capture the Tolkien spirit though it uses most of his devices of language, naming, plotting, etcet. As a matter of fact, some of these copies are a little too close for my taste – the hero takes the pseudonym of ‘Underhill’ and the dragon is identical with Smaug and his compatriots. The surprise ending spoils what effect has been built up throughout the story – any Tolkien imitation requires a sense of Fate and a mythic awareness; a surprise ending always kills them. But I hope the reception to this slightly botched Tolkien imitation doesn’t sour the editors on the type.’

Now I don’t know about you but I certainly never expected to find a phrase like ‘slightly botched Tolkien imitation’ to be used in connection with the author of the Earthsea books. However, while it’s a blunt assessment I can see why Evers thought what he did and I can’t really disagree with him. On the whole it was certainly for the best that Le Guin didn’t continue writing about Earthsea in this way. On the other hand, given some of the fantasy trilogies which were to come in the 80s I have to shudder slightly at the hope for more Tolkien imitations.

Oh, and in regards to the interlineation in the scan above, according to my research smog is a term that dates back to at least the early 1900s it’s not unreasonable to wonder if Smaug is a pun based on the term. I rather doubt it though as Tolkien’s etymology of Middle-Earth is, or is as far as I’m aware, based on far older languages and words. Still, was an interesting guess.

Tolkien was not by any means above the kind of joking that Smaug/smog would represent. Consider Sam’s cousin, Halfast Gamgee.

LikeLike

My thought wasn’t that Tolkien wouldn’t include humour in his work but that smog would be too recent a term for his liking. Not only that but it would probably bring to mind thoughts of industry and progress to Tolkien and I suspect he wouldn’t like that. My impression is that he would prefer 8th century jokes about bears.

LikeLike

I don’t think “half-assed” or “half-arsed” is a British expression, and Halfast is called Hal, not Half, suggesting the syllable break is after the L. I suspect Tolkien didn’t intend that to be funny any more than he meant the Hill of Túna to be funny. And “Smaug” doesn’t rhyme with “bog” — the “au” sound rhymes with “now.”

LikeLiked by 1 person