WORST SCIENCE FICTION STORY EVER!!!

It is my impression that Brian Wilson Aldiss was generally considered to be a stern but fair elder statesman until he passed away in 2017. I, on the other hand, considered him to be far more curmudgeonly than that (he would never have a passable member of the Beach Boys for example). It also my opinion that Brian Aldiss adopted his curmudgeonly persona relatively early in his career. Oh, but Doctor Strangemind I hear you all cry, Brian Aldiss was never a curmudgeon, at least not until he was old enough to carry the title with a suitable level of gravitas! Ah ha, my poor innocent audience! You have fallen into my cunningly constructed audience trap and now while you lay squirming in the metaphorical mud at the bottom of the pit of unwarranted assumption I’ll just sit here on the lip above and tell you all about how in Australian Science Fiction Review #15 (published by John Bangsund in April 1968) that young curmudgeon, Brian Aldiss, did go so far as to accuse two fellow British authors of writing as he put it the, ‘WORST SCIENCE FICTION STORY EVER!!!’ To quote from Aldiss himself:

There was one story in particular in Authentic which, ever since I read it on its first appearance in 1954, had impressed me as reaching a really impressive level of badness. To my great delight, I found on reading it again that it has grown even worse over the intervening fourteen years. I therefore would like to nominate as the worst sf story ever published:

The Lava Seas Tunnel, by F.G. Rayer and E.R. James, (Authentic SF, edited by H.J. Campbell, Vol.1, no.43, March 1954.)

Now before I unleash the savage beast that was Brian Wilson Aldiss I think it only fair I let F.G. Rayer and E.R. James put forward their side of the story. For the record, according to material published in Space Diversions, the fanzine of the Liverpool Science Fiction Society, F.G. Rayer and E.R. James were in fact cousins. Francis George Rayer and Ernest Rayer James, to give them their full names, had quite a few stories published in various British science fiction magazines during the fifties. My impression is that their work was used as filler material, inserted into gaps by editors such as Herbert J. Campbell (Authentic Science Fiction Monthly) and John Carnell (New Worlds Science Fiction, Science Fantasy, & Science Fiction Adventures) when nothing more impressive was to hand.

If I am correct then this would explain why F.G. Rayer felt that the science fiction being written in his day was not up to scratch and that much of the blame for this could be placed at the feet of editors. Consider this extract from an autobiographical article by Rayer in Space Diversions #6 (April/May 1953):

The present trend in S.F. has several admirable traits and several that are deplorable, Unfortunately a writer can do very little to influence such trends – the onus rests on editorial shoulders. If the editor does not like what the writer sends in, then he does not publish it. Accordingly the writer is usually committed to write, from time to time, stories which he deduces the editor will like. These are published. The others fill the W.P.B.

Well that’s as blunt a condemnation of the editorial fraternity as you are ever likely to encounter. A cynical person might also suspect this is an attempt by Rayer to divert potential future criticism away from what he knows to be weak stories. On the other hand he might be genuinely frustrated the refusal of Bert Campbell and John Carnell to buy what he, Rayer, considers to be his best material. Without more source material to hand it’s impossible to say one way or the other.

Okay, so what were the traits in science fiction that F.G. Rayer found so deplorable? I’m glad I asked. Again from the article in Space Diversions #6:

Deplorable traits, in my view, include:- women dragged into stories for the sake of the feminine or romantic interest; pictures of the later undressed yet unfrozen in space, etc; stories based on a series of “clever” incidents which do not really integrate.

I was disappointed when I read this as given his earlier comment I was expecting a more impressive list of complains than this. While I agree that illustrating partial nudity in space is never a good thing Rayer’s first point has to me a ‘No Girls Allowed’ vibe to it and not much else while his last is insufficiently explained for it to make much sense. On the other hand his list of positive traits paints a much clearer picture:

Admired traits are:- real originality, fully reasoned and logical development, scientific premises which will stand pondering upon, and lack of superficial emotion.

At this point in the article I began to wonder if Rayer wasn’t a scientific boy scout more in tune with the philosophy of Hugo Gernsback’s explaining science through fiction than where science fiction was actually heading at the time. A idea reinforced by the following:

These feelings, strong as they are, may have arisen from the large amount of work I do on electronic equipment; here, there is always a reason, although sometimes complex deduction is required to discover it.

That seems to sum up F.G. Rayer so what about E.R. James? Well in Space Diversions #7 (December 1953) there is an article by James called Don’t Shoot the Writer which begins thus:

He’s doing his best, and –

You’ll serve yourself and him much better if, instead of saying WHAT A ROTTEN EFFORT! you try to tell him where he has gone wrong from your point of view.

It takes a keen and knowledgeable mind to criticise constructively and with proper humility, for –

Criticism is a favourite occupation of mankind (and womankind.) But it is a two edged sword. If we say a story, a piece of music or even a meal dished up by an unfamiliar cook is no good, then we are expressing a relationship, not a truth. We are saying that we cannot digest the meal, the music or the story that has been prepared and, although it may be the author, the musician or the cook, it may also be merely a statement of our own limitations.

Eating fried snails, listening to symphony music and reading science-fiction are all acquired tastes. Even reading is not a natural ability (such as eating, seeing sleeping, etc.) For we had to learn first single letters, then words and finally abstract ideas which were behind those collections of words. So you see that reading, especially in respect to a single branch of reading, i.e. S-F., is almost – – though not quite – – as much a skill as writing the words to read.

E.R. James then spends a couple more pages expounding his ideas on what an author needs to do in order to write a good science fiction story. However I don’t think we need to go into that here and now for we have what we want. Certainly I do because to me these opening paragraphs read like an attempt by E.R. James to construct a Get Out Of Gaol Free card. You don’t like one of James’ stories, ah well reading science fiction requires special skills that perhaps you don’t have.

It’s especially telling that he starts off by assuming that the disgruntled reader will respond in a singularly inarticulate manner. It ensures your argument is easier to make if you can frame the opposing argument in as crude and clumsy terms as possible. Which is why the above extract from Don’t Shoot the Writer contains no hint that a reader might follow ‘What a rotten effort!’ with an unprompted and articulate explanation as to why they found the story rotten.

I think it’s also pretty clear that James makes rather strange use of the term ‘relationship’ because he actually means opinion but doesn’t want to come out and write that because it will likely be a red rag to a bull in regards to the audience of this article. What James is suggesting in this camouflaged manner is that any negative comment is merely an opinion and as such can be dismissed because opinions aren’t the same as facts. This is indeed true but what James is trying to hide is that a negative comment can contain both opinion and fact.

All in all F.G. Rayer and E.R. James come across to me like characters in a Simon and Garfunkel song:

We are but two sad boys,

Though our stories always sold.

We did trade our souls to editors,

The purveyors of deplorable, heed not their promises.

All lies and jests…

Still a man hears what he wants to hear,

And disregards the rest.

And now at last we come to The Lava Seas Tunnel, featuring the combined writing talents of F.G. Rayer and E.R. James. So perhaps you would like to know what this story, sorry ‘WORST SCIENCE FICTION STORY EVER!!!’ is about. So, a plot summary is clearly in order.

The Lava Seas Tunnel opens in the cockpit of some sort of boring machine. We learn that it’s commanded by a Steve Martel who is nervous about the forthcoming operation due to a previous accident. Martel shares the cockpit with an unnamed communications officer with whom he is annoyed because the fellow arrived late. Below, in the nose of the machine is an observation officer named Hedgersley and the engine room is crewed by somebody called McGilligan. What then follows is:

They begin boring.

The machine halts due to a fault in the thermostat.

After two & a half hours work this is fixed and they begin again.

They bore for hours but then the machine breaks down again due to a blocked nozzle.

Martel and the communications officer are knocked out by the sudden stop but Martel recovers and pulls the communications officer to safety and in the process discovers it’s his son, Dave, in disguise. Martel is annoyed that Dave has snuck aboard but there is little he can do about it now.

Anyway after sixteen hours work the blocked nozzle is fixed and Martel decrees a six hour break before they begin boring again.

Martel discovers McGilligan has exited the machine and it busy digging diamonds as big as eggs out of the tunnel wall. There is a confrontation, McGilligan produces a gun and locks the rest of the crew in the store room and makes his escape with the diamonds in a life-balloon.

It’s during this confrontation and subsequent incarceration that we learn that the Earth has run short of coal and oil and needs to tap into lava deep inside the planet in order to generate power. Nice to learn at last why we’re all here.

Once the remaining crew break out of the store room they discover McGilligan has smashed the instruments in the control room. An hour is required to repair everything sufficiently to begin boring once more.

Eventually they stop for a sleep break but Martel wakes up to discover he has been tied to his chair. Hedgersley then informs him that he works for a foreign country that wants to see this project fail. Hedgersley then escapes in the second life-balloon. Martel eventually escapes from his bindings just in time to discover Dave recovering from a blow to the head. He also discovers that Hedgersley has jammed the release mechanism of the one remaining life-balloon, trapping father and son forever.

The two of then make one last attempt to break through to the sea of lava the world so desperately needs access to. And they do! Success! But oh no, the borer is slipping down towards the molten sea where neither it or the remaining crew can survive. But fear not, Dave reveals that he also noticed the jammed release mechanism and repaired it. The two men scramble into the cabin of the life-balloon and float up the tunnel as the borer falls to its doom. Presumably they reach the surface and everyone receives their just deserts. The end.

So, Brian Wilson Aldiss, what’s your initial reaction to The Lava Seas Tunnel?

Anyone who has followed the careers of these two authors as closely as I have will know how exquisitely poor they can be alone; together, they are exquisitely bankrupt.

To be honest, Brian, I think exquisitely incomprehensible would be a better description. Almost nothing described in this story makes any sort sense. Consider the following account of how the boring machine works:

Turbines whined and flames glowed redly through the observation ports of indestructible mica. Below them, the rock made molten by the huge flame projectors was being sucked away. It would be ejected upon the walls of the boring, giant sprocket holes being formed in it as it solidified, so that the machine could wind itself back up to the Earth’s surface.

Okay, so two points I’d like to query about this astonishing process. First of all how is there an open tunnel behind the borer? Surely once the rock melted by those huge flame projectors is sucked back behind the machine it would solidify into the same amount of mass as it had before being melted? Secondly, just how are those giant sprocket holes being formed, hmm? You know, coming from somebody who claimed he wanted to see ‘scientific premises which will stand pondering upon’ this gibberish is especially embarrassing to F.G. Rayer. Don’t you agree, Brian?

This total blindness to any sort of technological probability extends to the equipment of the machine itself. The escape apparatus consists of three inflatable balloons, which are suppose to drift up the tunnel the boring machine has made! The machine is not refrigerated; it has “heat-batteries” instead. Nor is it equipped with an intercom; Hedgerley’s voice comes “over the reproducer”.

Yes, Brian, those life-balloons worried me too. At first glance the balloon idea is a potentially clever low-tech solution to the problem of how crew members might return to the surface in an emergency. However, as with all the technology mentioned in this story, there is no detail explaining how it works so I’m left high and dry. Given from what little the reader is told I’m guessing that the tunnel created by the borer is relatively smooth-walled (apart from those inexplicable sprocket holes that is) so in theory a balloon might float up the shaft unimpeded like a car in an elevator. By all rights however conditions outside the borer should be extremely hot so the balloon would need to be constructed of heat resistant material and filled with incombustible gas for it to be viable and we never learn if this is so.

You’re also probably right about the borer not being refrigerated but we can’t be absolutely certain of that because while the authors make it clear that the temperature inside the machine is being regulated they are once more singularly vague about how this is achieved. For example they do mention heat-batteries but give absolutely no indication of what heat-batteries do.

What actually worried me more is the inconsistent attitude of the authors to heat in general. Look at how they have McGilligan exit the machine in order to collect diamonds. By this point the borer was deep within the Earth’s crust and surely even back in the early fifties it was clear just how hot the inside of that tunnel would be. According to a video I watched recently about the Kola Superdeep Borehole in Russia the temperature in that shaft reaches about 180C/356F at 12,262 metres/7.6 miles. Inside the tunnel in this story the temperature would surely be at least that high, and that’s not taking account of the heat generated by the rock melted by those flame projectors mentioned earlier. It rather makes a mockery of the idea that the molten rock would cool enough to be used as the walls of the shaft, or that anybody could exit the borer without being cooked alive. Apparently the temperatures inside the shaft were determined by the author’s convenience rather anything approaching physics.

In regards to the internal phone system, Brian, I think your complaint is nitpicking given it’s initially described as an internal phone. I’m willing to accept that the device is also known both as a phone and a reproducer and is sometimes called the latter. For what it’s worth the reproducer was one of the less confusing devices mentioned since its purpose in quite clear, unlike the heat-batteries or the radar scanner.

Okay, so on to another of Brian’s major points:

For the assumption behind the story is that things are really desperate on Earth: all supplies of coal and oil have run out, and the only thing that will power Earth’s “enormous industrial machines” is lava. The authors literally have not heard of nuclear or hydro-electric or solar power.

If I was to be more generous than Brian I would assume this story was set on an alternative Earth where the power of the atom had not been discovered. However, even if I did the authors this favour the fact remains that the story is so bereft of context that I’ve no idea if it’s suppose to be set in our future or an alternate history. The authors included no details about the world outside of the borer, we never even learn who Martel and his crew work for or how the project is being funded. All we have are three surnames; Martel, McGilligan, Hedgersley, and one first name in Dave. I dare you to pinpoint their country of origin from those scant details. Given all this I can’t do them the favour of assuming they live in a world where nuclear power hasn’t been discovered.

Besides which, even if I did give the authors the benefit of the doubt in regards to nuclear power there still remains the vexed question of hydro-electric or solar power. Indeed I would go one further than Brian and mention the absence of wind, geothermal, and tidal power generation. How can it be that none of these things rate a mention in The Lava Seas Tunnel? One sentence gentlemen, one sentence was all that was needed to explain how the various renewable sources of power combined were nowhere near enough to keep Earth’s industry functioning. Add a second sentence and tell us how much cheaper lava power would be in the long run. We might not believe it but at least it would be possible to believe the pair of you have some understanding of how power is generated.

It would also help to explain why Hedgersley’s foreign employers were so keen to sabotage the boring project. Perhaps then these unnamed foreigners could be worried that this project would allow the unnamed backers of the boring project to hold the world to ransom and become Earth’s stern and unforgiving masters. Doing that would have given the story a little of the colour it so desperately needs.

Anything else, Brian?

The authors’ reluctance to come to grips with anything that might be termed a fact means that they do not tell us at the beginning that this is a four-man boring machine. This, coupled with their haziness of characterization, causes difficulty for the reader. It seems as though the machine is swarming with crew – ratings maybe, since the only people mentioned are officers.

Well, Brian, while I didn’t find the number of crew members confusing as you apparently did I still think you hit the nail on the head with your point about the authors not wanting to come to grip with facts. If The Lava Seas Tunnel can be said to have any defining characteristic it’s an air of purposeful vagueness. No attempt is made to ensure anything in this story seems real which guarantees there is no sense of consequence. It doesn’t matter what happens to any of the characters because they aren’t people and it doesn’t matter what happens to the world because it doesn’t exist.

Was Brian Wilson Aldiss right to label this as the ‘WORST SCIENCE FICTION STORY EVER!!!’? I can’t say because there is a lot of competition for that dubious honour. However, given the comments quoted at the beginning of this article, I would nominate F.G. Rayer and E.R. James as the most delusional science fiction authors ever.

And that’s saying something!

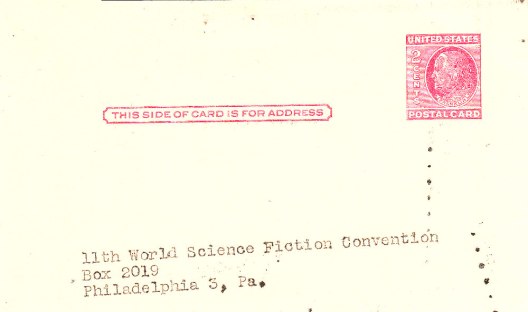

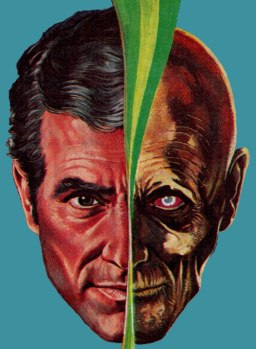

Hugo winner of all time, the novel They’d Rather Be Right by Mark Clifton and Frank Riley, has been more one of sorrow than anger. In the years since this novel was given the Best Novel Hugo in 1955 there have been two schools of thought in regards to They’d Rather Be Right. One is that it’s a mediocre novel that didn’t deserve to win a Hugo and the other is that it’s an underachieving novel that inexplicably won a Hugo.

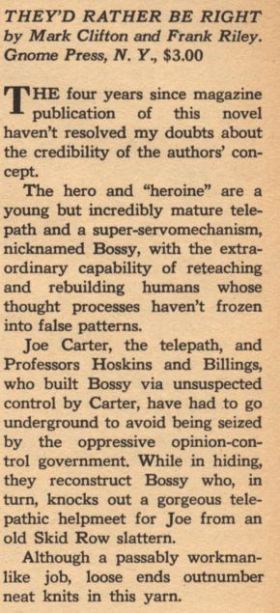

Hugo winner of all time, the novel They’d Rather Be Right by Mark Clifton and Frank Riley, has been more one of sorrow than anger. In the years since this novel was given the Best Novel Hugo in 1955 there have been two schools of thought in regards to They’d Rather Be Right. One is that it’s a mediocre novel that didn’t deserve to win a Hugo and the other is that it’s an underachieving novel that inexplicably won a Hugo. Admittedly, as my friend Mark Plummer has pointed out, all the professional reviewers in the science fiction magazines had something to say, but how much were their reviews duty and how much real enthusiasm? Look at the review by Floyd C. Gale published in Galaxy Science Fiction, July 1958 to the right. Hardly a ringing endorsement, is it?

Admittedly, as my friend Mark Plummer has pointed out, all the professional reviewers in the science fiction magazines had something to say, but how much were their reviews duty and how much real enthusiasm? Look at the review by Floyd C. Gale published in Galaxy Science Fiction, July 1958 to the right. Hardly a ringing endorsement, is it?