So just what happened in 1955?

Despite the battle in recent years over what works should be on the voting shortlist the Hugo awards have been relatively free of controversy since they were first awarded at the 11th Worldcon way back in 1953. Sure, I doubt there’s ever been a Hugo awarded in any category that absolutely everybody thought was well deserved. I don’t rate that as controversy though given the Hugo Awards are decided by popular vote and the disparate individuals who have voted on them each year naturally held many divergent opinions as to what constituted the best. To rate as controversy in my book there has to be some disagreement about how the awards have been run or how a particular winner was decided.

Off the top of my head I can think of only two instances that came anywhere close to plunging even a tiny slice of all fandom into war. One involved a well-known and extremely volatile author who became upset in the sixties because a particular worldcon committee was planning to not include the Dramatic Presentation Award (the committee eventually changed their minds). The other was a negative reaction in the seventies to what was seen by some as block voting for a particular fan artist (the artist decided to remove himself from future award contention).

Given all this perhaps it’s not surprising that the typical reaction to the most inexplicable  Hugo winner of all time, the novel They’d Rather Be Right by Mark Clifton and Frank Riley, has been more one of sorrow than anger. In the years since this novel was given the Best Novel Hugo in 1955 there have been two schools of thought in regards to They’d Rather Be Right. One is that it’s a mediocre novel that didn’t deserve to win a Hugo and the other is that it’s an underachieving novel that inexplicably won a Hugo.

Hugo winner of all time, the novel They’d Rather Be Right by Mark Clifton and Frank Riley, has been more one of sorrow than anger. In the years since this novel was given the Best Novel Hugo in 1955 there have been two schools of thought in regards to They’d Rather Be Right. One is that it’s a mediocre novel that didn’t deserve to win a Hugo and the other is that it’s an underachieving novel that inexplicably won a Hugo.

Back in February of 2011 Rich Coad published Sense of Wonder Stories #5 and in that issue of his fanzine he included a cleaned up version of an e-list discussion in which the participants discussed Mark Clifton, Frank Riley and even made some attempt to explain why They’d Rather Be Right won the 1955 Hugo. It’s quite an interesting discussion despite the way (or perhaps even because) it rambles from topic to topic so if you’re interested a PDF of Sense of Wonder Stories #5 can be found on eFanzines.

Anyway, after reading that e-list discussion I did some research of my own and eventually developed a theory (oh what a surprise) which I’ll share with you here. First though I’d like to point out that while I’ll make what I think are some interesting points, these can only be considered tentative without any input from the fans who voted in 1955. Unfortunately asking those fans is a tad difficult given most of them are no longer alive enough for the likes of me to bother them. What I did instead was the next best thing and examined the historical record. In other words I went and looked through all the fanzines I have in my collection to see what was being written about They’d Rather Be Right back in the 50s.

Unfortunately my collection is not nearly so complete that I can describe the results of this search as being definitive but I do like to think that what I did discover carries some weight. For starters I was only able to find two references to They’d Rather Be Right but interestingly they’re both at odds with the more recent opinions. In Fantasy-Times #214 (January 1955) Thomas Gardener in his annual review of print science fiction describes They’d Rather Be Right as the best novel of 1954 and in Etherline #45 (1955), ‘So far, it’s excellent!’ is the opinion of Tony Santos in regards to the first instalment of the serial in Astounding. Now two positive comments isn’t a lot to go on but it still suggests the novel had a few fans back when it was first published.

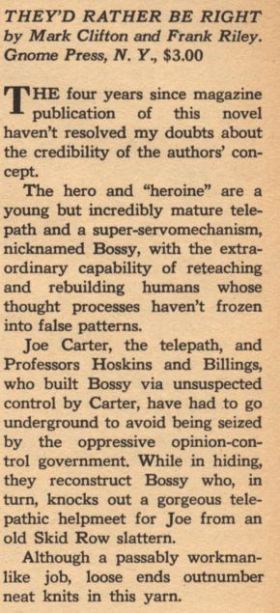

Admittedly, as my friend Mark Plummer has pointed out, all the professional reviewers in the science fiction magazines had something to say, but how much were their reviews duty and how much real enthusiasm? Look at the review by Floyd C. Gale published in Galaxy Science Fiction, July 1958 to the right. Hardly a ringing endorsement, is it?

Admittedly, as my friend Mark Plummer has pointed out, all the professional reviewers in the science fiction magazines had something to say, but how much were their reviews duty and how much real enthusiasm? Look at the review by Floyd C. Gale published in Galaxy Science Fiction, July 1958 to the right. Hardly a ringing endorsement, is it?

Okay, so if the enthusiasm for They’d Rather Be Right melted away faster than an ice cream on Venus then why oh why did it manage to win an award?

The Sense of Wonder Stories discussion touches on three possible reasons as to why They’d Rather Be Right won despite so little evidence of enthusiasm for it. Of these I don’t find the suggestion that it was carried over the line by a block vote from the Dianetics supporters very convincing. Given Dianetics was going through a very exciting early growth spurt at this point I doubt anybody but those members who were also science fiction fans would be concerned about a fledgling set of science fiction awards. I’m willing to believe that some, if not all, the various fans who were also into Dianetics could and did vote for They’d Rather Be Right but that’s all. I’m pretty sure that if any of them had tried to organise a block vote there would be some evidence of that. I’ve seen no mention of anything like a push to secure a Hugo for They’d Rather Be Right in any fanzine I checked and I’m certain that if anybody had tried to organise such a push rumours about the attempt would be published everywhere regardless of proof.

On to the second possible reason and not having access to any issues of Astounding from the relevant period I don’t have any evidence that John Campbell actively promoted They’d Rather Be Right for the Hugo (besides which, it wouldn’t be a good look to offer too much support) but it wouldn’t surprise me in the least if he at least put in a good word for it. Even putting his infatuation with Dianetics to one side, a win for a novel serialised in Astounding wouldn’t hurt his ego. Winning awards, even vicariously, feels good and is also the sort of news an editor likes to pass on up the corporate ladder to those paying his wage. I still doubt there was anything approaching a block vote for They’d Rather Be Right but if the novel was suggested for the award anywhere it was probably in the pages of Astounding. If nothing else John Campbell would surely be happy to stop Horace Gold, his editorial rival at Galaxy and regular sparring partner, from winning with the Frederik Pohl and Cyril M. Kornbluth novel, Gladiator At Law.

This brings us to the third and most interesting suggestion, that They’d Rather Be Right gained the inside running because the overall vote was split between multiple candidates. This idea wasn’t properly pursued in the Sense of Wonder Stories discussion, mostly I think because so few possible alternatives to the Clifton/Riley novel were brought up in that discussion. However that paltry list of rivals was based upon two false assumptions, that what fans in 2005 remember as being the good novels of 1954 were the same as fannish opinion in 1955, and that voters in 1955 had a clear idea of what was eligible. This is where a little more research can make a lot of difference (even if your references are incomplete like mine).

For a start the picture I received by looking through my fanzine collection is that the field of potential candidates was much larger than assumed in the e-list discussion. During 1954/55 the following novels received positive book reviews in at least two different fanzines: Gladiator At Law by Frederik Pohl and Cyril Kornbluth, Messiah by Gore Vidal, Hell’s Pavement by Damon Knight, Against the Fall of Night by Arthur C. Clarke, I Am Legend by Richard Matheson, Fury by Henry Kuttner, West of the Sun by Edgar Pangborn, The Kraken Wakes by John Wyndham, The Caves of Steel by Isaac Asimov, and A Mirror For Observers by Edgar Pangborn. I’ve not read everything on this list but of the novels I have read there are none I would rate as unworthy of a Hugo nomination.

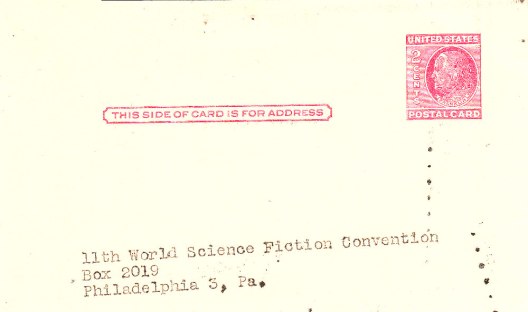

Now the key fact to note here is that until 1959 there was no filtering process in place to winnow down the number of options. It wasn’t till then that a worldcon committee decided to have voters first nominate which novels should appear on a short-list and then vote on that. Before that each committee would simply include ballots in their progress reports. The example I have here is a 1953 ballot taken from Progress Report #4 published by 11th Worldcon. By the way, the progress report I took it from was addressed to T.L. Sherred but couldn’t be delivered for some reason and was returned to sender. Thus I was the first person to lay eyes upon this ballot since it was originally sent out all those years ago (I do hope T.L. Sherred still managed to get his vote in). Anyway, as far as I can tell the 1955 ballots were essentially identical to this 1953 example:

Now, given such a crude system I can see how those novels listed above probably took votes away from each other. Books like Messiah or I Am Legend had no chance of winning but that doesn’t mean they didn’t receive a few votes regardless.

Now of course some of you will be falling over yourselves to point out to me that not all the novels listed above were eligible for the 1955 Hugo and you will be right. This indeed was surely part of the problem because those who voted in 1955 didn’t have access to most of the references we do. For example a quick search online shows me that The Kraken Wakes was first published in 1953 and thus was ineligible (depending on whether the Cleveland Committee counted foreign publication or not). Somebody who bought their copy of the Wyndham novel from one of the book dealers listed in Fantasy Advertiser might not be aware of this and vote mistakenly. Even if we assume every voter did a little checking and took care to not choose any clearly ineligible novels I bet errors were still made. As Mark Plummer notes in his Sense of Wonder Stories #6 letter, the period of eligibility wasn’t a calendar year but ran from August to August. That would be easy if all the above examples had seen magazine publication but as some hadn’t voters would have to decide eligibility by whatever year was quoted in the copyright notice at the front of whichever book they happened to possess. I expect the Cleveland Worldcon Committee culled out any errors they spotted since I assume they knew what was eligible and what wasn’t but that doesn’t entirely negate the problem. Every mistaken vote cast reduces the (probably) small number of votes and makes it just that much easier for John Campbell to potentially encourage the readership of Astounding to roll right over the rivals to They’d Rather Be Right.

It has become clear to me that the key to the win by They’d Rather Be Right was the mechanics of the voting system. I see that Mark Plummer also mentions in Sense of Wonder Stories #6 how Nycon II, the 1956 worldcon, wanted ‘a more representative vote’, which I suppose could mean anything but which I suspect is a tacit admission that the 1955 votes were spread between too many candidates. It’s not too hard to imagine the Nycon II Committee hearing from the Clevention Committee about how They’d Rather Be Right beat out out the likes of Gladiator At Law despite the latter being a better regarded novel because so many other books received votes. It’s also possible that some of the Clevention Committee didn’t approve of certain novels getting voted for at all, Messiah and I Am Legend come to mind in this regard, and wanted something done to discourage future voting for novels like those.

On a side note it’s worth noting that as per speculation in the Sense of Wonder Stories #5 Mark Clifton had a pretty high profile in 1955. Not only had he written a number of well liked stories but he also had an article about writing science fiction in the ninth issue of Ron Smith’s fanzine, Inside (May 1955), a fanzine to which fandom was clearly paying attention as it won the Fanzine Hugo in 1956. Oh, and according to various issues of Fantasy Times Mark Clifton attended several conventions in the mid-fifties and was announced as one of the speakers at the 1955 Worldcon. I’ve no idea if he did turn up and speak but just the news that he would be there no doubt helped ensure that nobody forgot he existed.

So let that be a lesson to you all. Regardless of how you feel about the current nominating and voting process for the Hugos you still have it better than they did in 1953. I suggest you lull yourself to sleep at night with that thought.

Minor point: the title of the John Wyndham book is – and I think always has been – “The Kraken Wakes”. As for your theory, it makes sense but it would help the argument if the voting numbers were actually available; I guess that there are no surviving records.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have a blind spot in regards to that Wyndham novel and always seem to get the title wrong. Well, fixed now so thank you for pointing it out.

If there were any surviving records I imagine we wouldn’t still be debating the matter all these years later. Unfortunately none of the committees running the early worldcons had an eye to the future. Whatever records were made at the time don’t appear to have been kept once the convention was done and dusted.

LikeLike

‘Now the key fact to note here is that until 1959 there was no filtering process in place to winnow down the number of options.’

You’re a bit out of date here, Doc. I mentioned in my letters in SOWS#6 that the Nycon committee said they planned to have a nomination phase and it’s now been decided that there was a short-list for the 1956 Hugos, hiding in plain sight in that Worldcon’s PR3. See: http://www.thehugoawards.org/hugo-history/1956-hugo-awards/. Obviously this doesn’t relate directly to the 1955 decision.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I should be noted that I was taking Peter Weston’s word for this as he stated as such in the original discussion in Sense of Wonder Stories #5. Anyway, this new information reinforces my point about the Cleveland situation influencing subsequent worldcon committees. So what happened in 1957 and 1958?

LikeLike

I first discovered science fiction in 1956. Around then, someone donated a lot of science fiction magazines to the local library, and since they had no use for them, they let another kid and me take whatever we wanted. I truly don’t remember reading the story in serial form and certainly don’t have any opinion on its literary merit.

But I have always remembered the basic premise of the story and even the title (for me that is saying a lot). I have quoted the title and described the (very basic) plot to other people multiple times since then. I believe that it actually was one of the formative concepts in my developing view of society and the world. So, great literature or not, I wonder if perhaps other people were influenced as I was. This was the era of McCarthyism too – I wonder if that played a part in the popularity of the book as a reaction against dogmatic bias and prejudice.

LikeLike

I certainly wouldn’t be surprised if this novel did indeed speak to a lot of people in the fifties about the politics of the day. I should also probably mention here that John Campbell claimed that he was told more than once by readers that Astounding was one of the few bastions of free thought in the US at the time the Clifton/Riley novel fits right into that idea.

LikeLike