The highest powers of imagination?

I imagine most of you reading Doctor Strangemind are familiar with Ambrose Bierce. At the very least you will know he wrote An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge as that is widely regarded as one of the most famous short stories in American literature.

You are perhaps even more familiar with Bierce’s longer work, The Devil’s Dictionary. Certainly just about everybody I’ve ever counted as a friend has been a fan of this satirical lexicon. Even people who aren’t dyed-in-the-wool cynics are often familiar with at least some of The Devil’s Dictionary.

It’s even possible that you are familiar with the story of how Ambrose Bierce disappeared without trace in Mexico, having last been seen in the city of Chihuahua in January 1914. Some have said this mysterious disappearance was a fitting end to a life that was as epic as any of the great stories Bierce wrote. I on the other hand prefer to believe that Ambrose Bierce took the opportunity while in Mexico to travel through time and reinvent himself as Philip K. Dick, but that’s just me and I wouldn’t trust me if I were you.

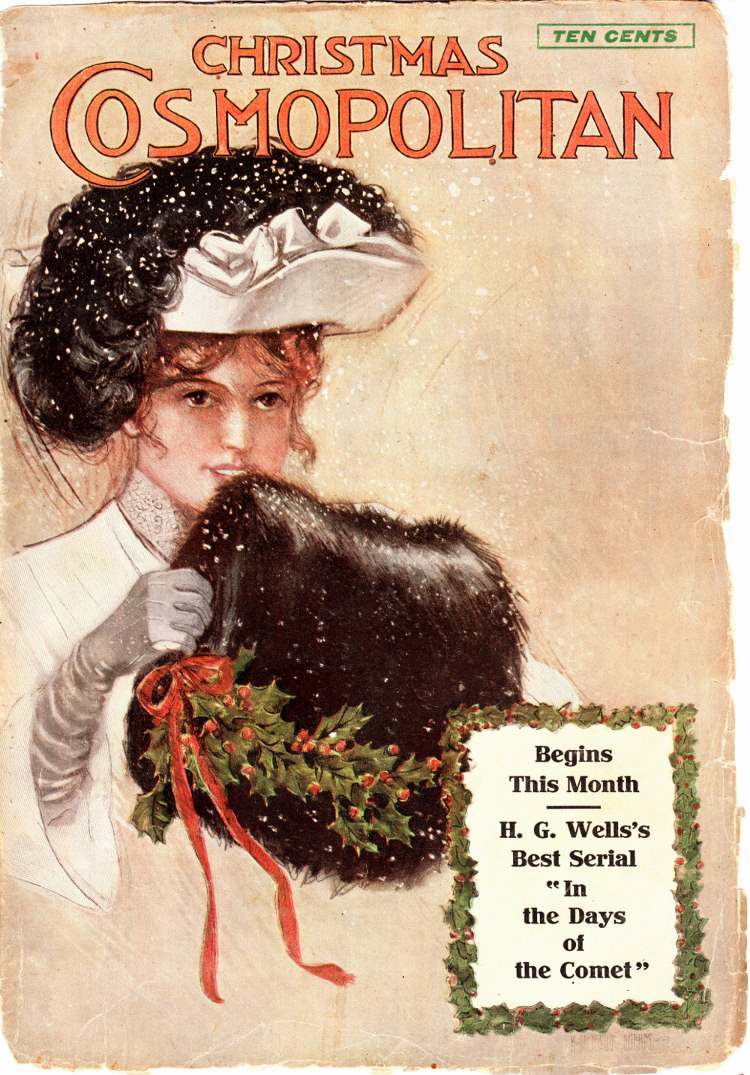

However what you are almost certainly unaware of is that well before Bierce entered Mexico and legend he was a columnist for Cosmo. Yes, that Cosmo, the thick and glossy fashion magazine you’ve seen on newspaper stands and in doctor’s waiting rooms more times than you can count. However Cosmo, or to give it its current proper name Cosmopolitan has been around longer than I bet you were aware. The Cosmopolitan was first published in 1886, which would make it one of, if not the oldest newsstand magazines in the world.

However, you need not fear that Beirce wrote the nineteenth century equivalent of those sex and fashion exposes that Cosmopolitan has been more recently known for. When The Cosmopolitan first appeared it was intended to be a ‘family magazine’, in other words a magazine which was suppose to entertain and educate the entire family (assuming the family was sufficiently well-off to afford the ten cent cover price).

From what I’ve read of Beirce’s column, The Passing Show, I can’t help but feel he was hired to keep the curmudgeonly old man demographic happy. This isn’t a bad thing mind you, it’s rather entertaining to read his grumbling about trends and the swatting of malefactors with his cane of good practise. This became doubly entertaining for me when I discovered him straying into one of my favourite genres of fiction.

In Cosmopolitan Magazine, Vol. XL No. 2, December 1905 he reacted to what he considered to be a hagiographic response to the death of Jules Verne:

The death of Jules Verne several months ago is a continuing affliction, a sharper one than the illiterate can know, for they are spared many a fatiguing appreciation of his talent, suggested by the sad event. With few exceptions, these “appreciations,” as it is now the fashion of anthropolaters to call their devotional work, are devoid of knowledge, moderation and discrimination. They are all alike, too, in ascribing to their subject the highest powers of imagination and the profoundest scientific attainments. In respect of both these matters he was singularly deficient, but had in a notable degree that which enables one to make the most of such gifts and acquirements as one happens to have: a patient, painstaking diligence—what a man of genius has contemptuously, and not altogether fairly, called “mean industry.” Such as it was, Verne’s imagination obeyed him very well, performing the tasks set for it and never getting ahead of him—apres vous, monsieur. A most polite and considerate imagination, We are told with considerable iteration about his power of prophecy: in the “Nautilus,” for example, he foreshadows submarine navigation. Submarine navigation had for ages been a dream of inventors and writers; I dare say the Egyptians were familiar with it before they

“heard Cambyses sass

The tomb of Ozymandias.”As well say that in “Rasselas” Doctor Johnson prophesied the modern flying machine, although one could remember Daedalus and Icarus if one would try. When Verne took his readers to the moon, he might have shown them, carved in the bark of a lunar sycamore, the name of Lucian, with the date—for Lucian was a cautious man–”Circa A.D.CLXXXVII.” Jules Verne was a lovable character and a good writer. The world, if no wiser, is better for his having lived and written; but to compare him with so tremendous a fellow as Mr. H. G. Wells is to stray into the beaten path of literary criticism and incur the plaudits of the respectable.

For the record I will note that Mr H.G. Wells was a regular contributor to The Cosmopolitan (and was indeed present in this very issue) so it’s not beyond the realm of possibility that Ambrose Bierce was was slightly biased towards somebody who was a valuable asset to his employer. I prefer to think however that Bierce was sufficiently independent in his attitudes that he wouldn’t write the above just to please an editor or the owner.

Besides which I have to agree with him in regards to Verne. I’ve only read a couple of books by Jules Verne but what I have read (Around the World in Eighty Days and Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea) isn’t what I would call ambitious. To me neither of them were novels so much as catalogues of wonders with a little plot to hold these viewings together. Jules Verne is certainly interesting from a historical perspective but that doesn’t make his fiction especially memorable.

A harsh assessment of Verne perhaps but as Bierce’s words above demonstrate, there is no romance or glory in criticism, not if you want to be honest.

While I agree with Bierce that Wells was a better writer than Verne, I do wonder if Bierce read Verne in the original French. Verne was notoriously VERY ill-served by his English translators until much later than 1905.

LikeLike

And as for COSMO, I have indeed seen some of those early issues, and it was much more of a general interest magazine in those days, also publishing a lot of popular fiction. They even had a book imprint.

LikeLike

I’m fortunate to own a number of early issues of The Cosmopolitan and I agree that the nineteenth century issues in particular are full of fascinating fiction and non-fiction. My prize issue has an installment of WAR OF THE WORLDS, my favourite H.G. Wells novel.

LikeLike

Given what I’ve read about Bierce and what I’ve read of Bierce’s own writings I suspect he would not be any more generous to Verne even if he had read the original French editions. The problem is that regardless of how well Verne wrote his novels they were still essentially travelogues in one form or another and my impression is that such a straightforward style of plot wouldn’t be held in high regard by Bierce.

LikeLike

Can I expand on Rich Horton’s point?

No doubt Bierce’s curmudgeonishness was justified by the poor translation and editing of many Verne works as available to him, but all credit to him for adding a reasoned consideration of Verne’s genuine virtues. Bierce wrote that Verne “had in a notable degree that which enables one to make the most of such gifts and acquirements as one happens to have: a patient, painstaking diligence… Such as it was, Verne’s imagination obeyed him very well, performing the tasks set for it … ”

That was a good insight by Bierce. In fact Verne’s imagination, buttressed by diligent thought, scored some notable successes which couldn’t be recognised in Bierce’s time.

In From the Earth to the Moon and Around the Moon (1865 and 68) I see the story events as amazingly close to humanity’s actual first Moon voyage, the 1968 Apollo 8 mission. Verne describes a moonshot using USA technology (not French or British); by a national organisation (not a backyard inventor); launch site Florida; a space vehicle launched by a giant booster (hmm, I’ll get back to this); a three-man crew; period of “zero gravity”; rockets for steering; route around moon without landing; splashdown in Pacific and retrieval by a US Navy ship. By comparison, Wells’ First Men in the Moon is fantasy (which Verne himself complained about). But my booster point isn’t right, you say. How about Verne’s launch booster being not a rocket but a Mother of all Guns? Simple. Verne knew what Americans liked.

In Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea and The Mysterious Island, Verne’s best prediction of the future is not the wonderful steampunk submarine but Captain Nemo, the sub’s enigmatic master. We know today that Nemo is a prototype Osama Bin Ladin, maddened by unjust imperialism and striking back at the West through its transport technology. But this was censored out of the original editions! The Science Fiction Encyclopedia tells us: “Over and beyond their travestying of Verne’s scientific descriptions of the world, the editing of both titles removed any imputation that Nemo had just cause to take revenge on the British who had invaded and corrupted his native India.”

Pity Ambrose Bierce never saw better translations of Verne’s work, or witnessed real-life events echoing the fiction. If he had, his article might have given better “appreciation” to Jules Verne’s imaginative power.

(Sorry went on so long. Even with all my evidence, I doubt that Dr Strangemind will be convinced…)

LikeLike

I fear you are missing the point Mr Redd if you think I need to be convinced of anything. In reality I am merely a bystander reporting on what has happened before his astonished eyes. The one you need to convince of anything is Ambrose Bierce and I fear that you would find changing that mind an uphill battle even if he were still alive.

LikeLike